Simple demonstration of slow and fast SKU forecasting

In December 2006 I presented seminar for the CILT on Supply Chain Inventory Management, and this very simple demonstration comes from that presentation. It is designed to highlight the different levels of forecast accuracy that we can achieve for slow and fast SKUs. (As I mentioned in my post from 29 Nov 06, estimating forecast accuracy is very important.) Anyone can do this – all you need is a standard pack of playing cards.

“The game is Louisiana Deal’em…”

Remove the jokers from the pack and shuffle thoroughly (if it’s a new pack this will take some time). It is important to get a randomised order in the deck.

Now deal 13 cards face up. Note down the number of red cards (hearts and diamonds) and the number of Aces.

Before you do this for real, answer these questions:

- How many Aces do you expect (your best estimate)?

- And how many red cards?

- How confident are you in your forecasts?

Doing this once isn’t going to show much, so we need to repeat the process until we’ve done it about eight times (we had each table in the seminar do this for us).

The Results

Here are some sample results – yours should look something like this:

| Trial # | Aces Count | Reds Count |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 2 | 8 |

| 3 | 2 | 6 |

| 4 | 3 | 7 |

| 5 | 1 | 7 |

| 6 | 1 | 6 |

| 7 | 1 | 5 |

| 8 | 0 | 5 |

| 9 | 0 | 6 |

| 10 | 2 | 8 |

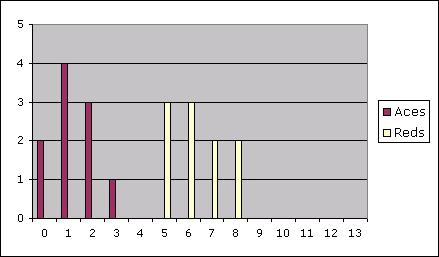

To make it easier to see what’s going on, I’ve also prepared a chart showing the relative frequencies of the various values for Reds and Aces.

Revisiting those questions

The first two questions are easy. I’m sure most people put their best estimates of the number of Aces to be 1 and of the number of Reds to be 6.5, or perhaps 6 or 7 if you only wanted to give a whole number answer.

The third question about confidence in the forecast is a little trickier. For a start, it doesn’t specify what form we expect the answer to take. Some people give a subjective description (“high” or “low”). Others give a percentage chance (“25% sure I’ll have exactly one Ace”). Others might quantify the chance of a range of values (“75% sure there will be between 5 and 8 Reds”). For the purposes of extracting some learning from this little demonstration, all of those are fine.

The answer we are looking for here is that the forecast for the number of Red cards is much more reliable than that for the Aces. If that’s not clear from your results, have another look at the chart. Look at the spread of results above and below our expected values. For the Red cards, all of the tests gave numbers that were within 25% of the forecast. Whereas over a third of the tests for the Aces gave values at least 200% of the forecast.

Implications for stock holding

Now imagine that each time we are dealing those 13 cards the number of Reds and Aces represents the weekly demand from our customers for two different products. It is easy to see that in order to maintain similar levels of service for both products, we would be planning on carrying much higher multiples of our weekly forecast for the slow mover – the Aces, which have a very unreliable forecast – than for the fast mover.

If we operate our supply chain with stock targets that are defined in terms of sales cover, and those cover targets are set to constants across the business or product categories, then we won’t be taking into account these slow-mover effects. Sometimes this may produce reasonable results – it may make sense to provide much lower stock availability on slow movers – but often it leads to uneconomic stock decisions and overstocks on high demand products.

Why should dealing cards be like customer demands?

Why indeed. Imagine all of our potential customers and all of our products. Every week, there is a small chance that each of those customers will make a decision to come to us for each product. Depending on the kind of business this is, this may be driven by some combination of whim, available cash or credit, what they bought last week, promotional activity by our business or our competitors, the breakdown of all or part of an existing product, the weather – anything.

We can never know what these chances are or exactly what drives them. All we see is the result: the customer demand for the product. But we do know that for faster-moving products the propensity to require the product is higher in some or all customers, and/or our potential customer base for those products is higher.

This is (more or less) what is happening with the playing cards. For each of the 13 cards dealt, there is a 50% chance it will be Red, and an 8% chance (1 in 13) it will be an Ace. For the statistically-minded, these are Bernoulli trials.

Statistical note

The mathematically-literate reader will have noticed that the playing card demonstration is not, strictly speaking, 13 independent Bernoulli trials. For that to be true it would be necessary to replace each card after it is dealt and reshuffle the deck. However, for a quick teaching demo, it is close enough. Apologies to those who like to get it right!

Links

Wikipedia’s entry on Bernoulli trials:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernoulli_trial

Categories: Training and Reference.

Tags: Forecasting

Comments: none